Even as a fourteen-year old boy, I knew something was wrong. I didn’t know exactly what was wrong, just that something was wrong. There was an unsettledness, my subconscious mind tugging gently “No” while logical brain wanted to say “Yes.”

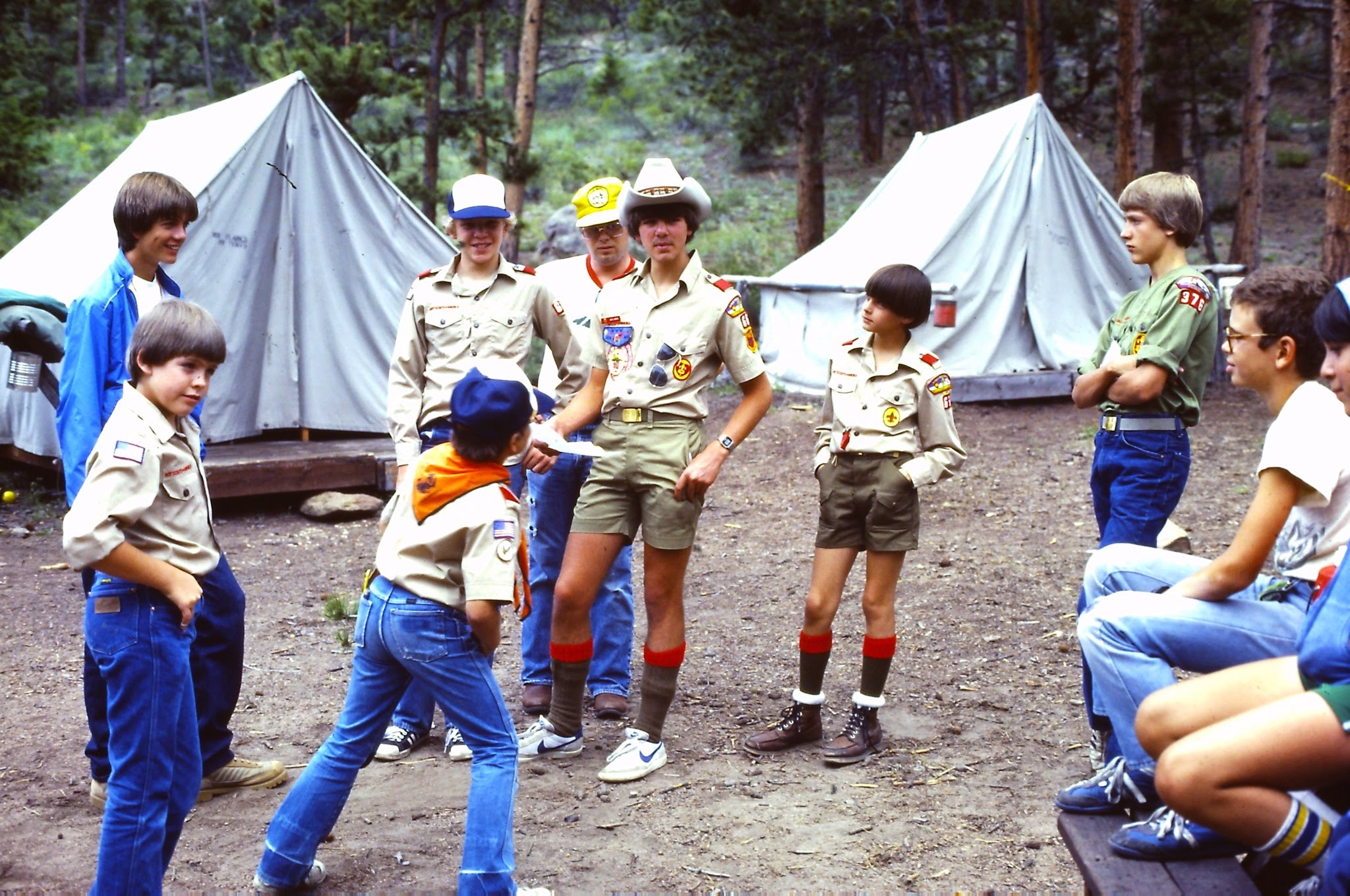

I was seated around a picnic table with a half-dozen other Boy Scouts, high up in the Rockies at the Ben Delatour Scout Ranch in Red Feather Lakes, Colorado. Situated just above the Poudre River Canyon, I was surrounded with tall pine trees, majestic rock formations, and the clear blue skies the state is known for.

Before this week at camp, I had never met my fellow Scouts. We came from troops across northern Colorado, Wyoming, and Nebraska and had been selected to attend a regional leadership development program called Troop Leadership Training or affectionately, TLT. [FOOTNOTE 1]

Our scoutmaster for the week, who had also been a stranger to me at the start of the week, had just presented a case study to our patrol: A group of boys had been tasked by their Scoutmaster to construct a pioneering project, lashing together thin poles from lodgepole pines with manila rope in order to create a sturdy structure.

Think monkey bridges and signal towers without nails or screws, just rope and wood. The Scoutmaster gave the instructions and then left the patrol to figure what to build and how to build it. Then, as now, Scouting is a youth-led movement, with adults acting as advisers.

Some of the boys in the patrol wanted to build a monkey bridge. Others wanted to build a tower. Some more outgoing boys expressed their ideas loudly and convincingly. Other boys remained silent. Without consensus, some of the boy were eager to start the project. They grabbed poles and started to lash them together and a tower soon began to take shape. As it did, a few of the other boys stepped in to help, but not all. They sat around and talked while the tower was being built. These were well-trained Scouts and they quickly used square lashings to build the outside of the frame and the diagonals to keep it sturdy. Once this phase was completed they scaled the outside of the tower and began to use floor lashings to build the floor. Then, the final touch — a tall flagpole atop the tower built with shear lashings, where they proudly displayed the patrol flag. It was then that the Scoutmaster returned and saw the beautifully-built tower, examined the lashings, and congratulated them on their work.

At the end of sharing that story, our Scoutmaster paused and asked us the question: “Was the pioneering project a success?” And that’s when my unsettledness started. I wanted to say yes, that the pioneering project had been successful. After all, the objective had been accomplished. The tower had been built, and built well. The job was complete. Meanwhile, another part of my brain was uncomfortable saying yes. Something wasn’t quite right about the project, but my fourteen-year old brain didn’t know what something was.

I wasn’t alone. Some of the other Scouts at our table were convinced that the tower was a success. Others were arguing that it was a failure. The more I listened, the more confused I became. Was it a success? Or a failure?

That’s when our Scoutmaster stepped in and taught us a simple tool called the Par-18 Evaluation System. It was a simple diagram with two axes, one labeled Task and other labeled Team: [FOOTNOTE 2]

Each was to be ranked separately:

- How well was the task accomplished?

- How did the team perform?

Beneath those big categories were three simple questions each:

- Was the job completed?

- Was it completed on time?

- Was it completed correctly?

- Did everyone in the group participate?

- Was everyone in the group pleased with the effort?

- Is everyone in the group eager for the next job?

Scouts were asked to rate each question from a one to a three — by consensus. If the project received all 3’s they total 18 — thus the name of the system.

It’s been more than forty years since that summer in the woods. I no longer remember how we scored the final project. But I clearly recall that’s when the gnawing in my brain stopped. Now that I had an evaluation framework, the answers came easily. The task — clearly a success. The team — not so much.